With Scott away at his crag course in Leavenworth, I wondered what to do with my weekend? Early Saturday morning, I drank tea and read from the anthology of Nature Writings. I watched the birds play and hunt in the water out my window. I wrote in my journal. I de-thawed some raspberries and ate them with granola and pecans and milk (yum). And then I decided to make soap. We were nearly out of the soap I’d made in November and I didn’t know when I’d have time again this spring. So, out went my relaxing, non-committal weekend of leisure. To my spreadsheets, my notebooks, and the internet – to decide upon the how-much and what-needs and when-how of my second-ever batch of soap!

I decided to make a triple batch, varying the flavours of soap from the previous batch but sticking to the same basic recipe so as not to change too many variables at once (that’s a good-scientist thing, though hard to stick to). I still had most of the basic oils I needed (coconut, palm, castor, olive), bought in bulk in November, but would need to buy again the expensive and luxurious vit-E-rich wheat germ oil as well as various essential oils for flavouring my batches. Of course, once in Zenith picking up my supplies, I couldn’t resist adding beeswax to my recipe as they had leftovers for sale.

For this batch, I wanted to try peppermint-tea tree with poppy seeds and a lemongrass-lavender with oatmeal and a touch of lime. I also decided to make again the cinnamon-rosemary, ‘cause we both loved it and I had leftover essential oils. At home Saturday evening I double checked my calculations and prepped all my flavours – measuring out poppy seeds and crushing dried peppermint leaves, grinding oats, and chopping fresh lavender and rosemary.

Sunday morning I lay down a dirty sheet on the kitchen floor, got out my balance and my pots, jugs, thermometer, and bowls, and began. Wearing a facemask, sunglasses, and gloves, I weighed lye and water, made the lye solution, and placed it in a cold water bath. Then the arduous task of weighing oils to melt on the stove. This actually is not that arduous at all except that the largest component of the recipe, coconut ‘oil’, is a hard solid below 76 F and quite difficult to scoop out of its container. Only afterwards, watching it melt on my hands, did I consider that I could have warmed it first.

Another surprise was that beeswax has a quite high melting point, compared with the other oils in the recipe. It doesn’t melt until 150 F which I just hoped wasn’t above the boiling point of the other oils. It wasn’t. When at last the beeswax was all melted, I had a clear brown oil in my ‘cauldron’, as I began to think of it. Of course it had taken me so long to scoop out the infernal coconut oil, and what with the beeswax needing such a high temperature to melt, my lye solution was now cooler than the oils. I improvised a hot water batch for the lye solution, resting the plastic jug on rocks in a pot of water that I brought to near-boiling.

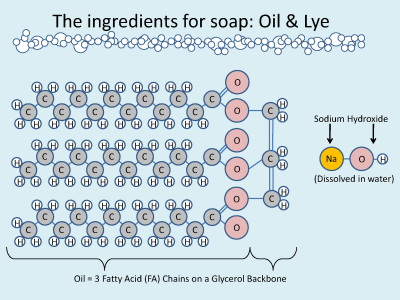

When the temperatures matched(ish), I poured the lye slowly into the oils, stirring. As they mixed, the solution turned yellow and opaque and began to thicken. I loved knowing that the oils were saponifying; sodium from the lye was attacking the triglycerides, removing the three fats from their glycerol backbone, making soap and glycerin. (Blah Blah blah blahblahblah, for you non-science-types). Within 15 minutes, the soap had ‘traced’ (you have to experience it to know it) and then it was crunch-time. This particular recipe sets relatively quickly and my adrenaline raced as I poured the still-saponifying oils into 3 bowls and began mixing in the respective fragrances and herbs. I worked quickly but when I ‘poured’ the third bowl’s contents into the molds after just a few minutes, it was more like pouring mashed potatoes than gravy. For molds I used a wax paper lined Tupperware box and tetrapaks from milk and chicken soup stock.

After dinner and a movie the soap smelled lovely and was ready for unmolding. I peeled the wax paper off the first soap block and then tore the cartons from the second and third batches (invest: exacto knife). I so enjoy cutting soap into bars. The soap at the end of the day is the consistency of cool fudge – you need a heavy hand to push the knife through the block, then you pry it off with a careful twist on the blade. And it’s so pretty and smells so good. I cut 62 bars, making my average cost/bar = about 98 cents. Not bad at all.

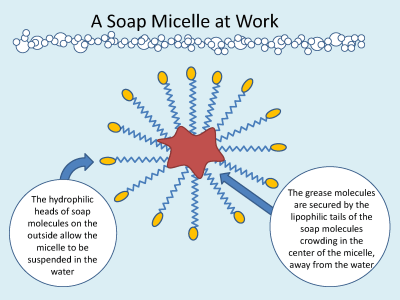

It took me about 3 hours all-told to prep, make, and clean up. I was a little pooped afterwards but it was utterly satisfying to see my little bars all lined up, curing atop the bookcase. During the next 4-6 weeks, the soap will get harder and the pH will drop towards neutral as the lye is fully used up reacting with oils to create soap and glycerin molecules. When I use the soap at first it’s special, and I admire each bar that I pull out of the cupboard. Later it’s just soap – it smells good, has good texture, and I know what’s in it cause I made it myself.

Cinnamon-rosemary

Peppermint-tea tree oil with poppy seeds

Lemongrass-lavender with lime, oatmeal and fresh lavender